The shortest is the Wall of Ca' del Poggio, the one of Prosecco: 1.16 km, with an average gradient of 12.3 percent and a maximum - a stiletto-like stab - of 18.

The longest is the Sellaronda, not one but four passes (Campolongo, Pordoi, Sella, and Gardena), a Dolomite loop (from Maratona dles Dolomites), total 51.6 km, more than half (26.3) uphill.

The most winding (and the one that goes highest) is the Stelvio: 48 hairpin bends from Prato to the pass with an average gradient of 7.5 in 24.8 km, up to an elevation of 2,757 meters.

The sweetest is the Poggio: 3.7 average gradient for 3.7 km from Aurelia to the balcony that smells of spring and from where one launches to conquer the Milano-Sanremo.

The most unpaved (and heroic) is Monte Sante Marie: from Asciano to Torre a Castello, 11.5 km climbing over 400 meters with two ramps at 18% and other heroic stretches.

The most numerous are those of Monte Grappa: ten slopes, a cycling park, each slope with its own physiognomy, altimetry, mileage, history, and charm.

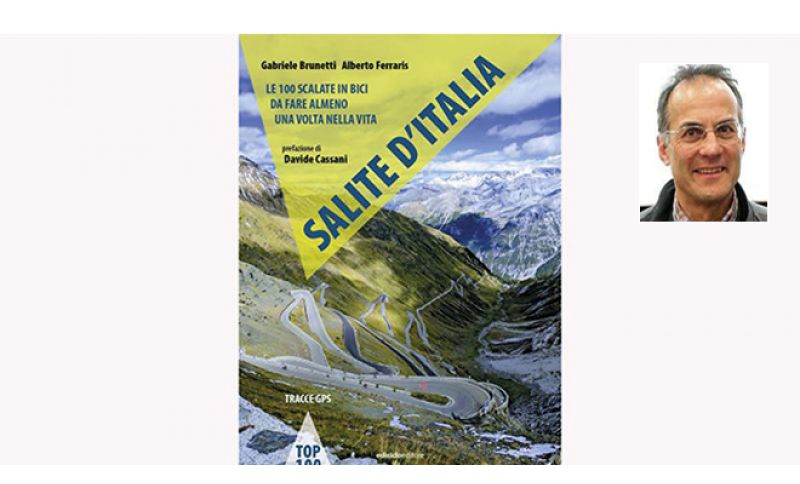

"Climbs of Italy", one hundred bike climbs to do at least once in a lifetime. From the book written by Gabriele Brunetti and Alberto "Lupo" Ferraris, introduced by Davide Cassani, GPS tracked and published by Ediciclo (272 pages, 25 euros) for Tuttobiciweb, Giuseppe Figini has already written about it (read HERE). But the work deserves, like all climbs, at least another point of view.

"I had my lightning bolt for mountains to climb by bicycle in 1976" - writes Cassani -. "I was fifteen, racing as a junior, and went on vacation to Moena. Felice Gimondi had just won his last Giro d'Italia. He was my idol. In the heart of the Dolomites, I didn't miss the opportunity to climb Pordoi, Sella, and San Pellegrino". Not everyone agrees. Jokingly, but not too much, Dino Zandegù claims he has never loved a climb, indeed, he wants to specify, "climbs should all be abolished, but risking abolishing the descents which are instead immune from blame", and he declares that "climbs are a crime against humanity". But it is true that climbs are not only ascents but also ascensions, that on a climb one strips away everything until discovering and protecting only the essential, that on a climb one settles accounts first and foremost with oneself, that climbs are the realm of fatigue, solitude, and silence. Cyclists go uphill as if attracted by an instinctive and primordial magnet, spectators go uphill to watch the riders to be able to admire them longer and also to understand how far human suffering can go, that sadistic relationship (on the part of spectators) and masochistic (on the part of riders) present like in no other sport.

To compile their ranking, Brunetti and Ferraris adopted various criteria: length, gradient, and difficulty, elevation and elevation gain, but also quality and safety, rewarding not one-way climbs but those in a loop. Therefore, "climbs were considered as a product". Except to specify that "the final ranking nonetheless reflects the authors' thinking, and for this reason has only an indicative value". In short: "It is not an official ranking". Because climbs also have affective, romantic, emotional, spectacular, geographical, natural, familiar, literary aspects. In a single word: sentimental.

And so the most religious climbs are those of Madonna della Guardia (near Genoa), Madonna del Ghisallo (in Lombardy), Madonna di San Luca (above Bologna), also that of the Sanctuary of Oropa (above Biella). And so the climb most linked to Bartali is Rolle, the most remembered by Massignan is Gavia (from Ponte di Legno), the most loved by Pantani is Carpegna, the hardest (or better: the one with the hardest section) is Colma with the Muro di Sormano, the most claustrophobic is Zoncolan (from Ovaro), the straightest (a straight line towards Capanna Bill that seems to never end) is Fedaia, the most volcanic is Etna (but there's also Vesuvio), the northernmost is Passo del Rombo (from Val Passiria to the Stubai glaciers, in Alto Adige), the southernmost is still Etna...