Since the world began, it has been turning life. The life of those who worked clay and made vases and amphoras. The life of those who pressed olives and extracted oil. The life of those who ground wheat and obtained flour.

Since traffic began, it has been turning carts and wheelbarrows, carriages and strollers, gigs and sedan chairs, chariots and diligences, cars and motorcycles, buses and minivans, vans and trucks, but also trolleys and skateboards.

Since bicycle began, it has been turning cycling. That of the road cyclist, slender. That of the track cyclist, smooth. That of the mountaineer, rugged. That of the pursuer, lenticular. But also those small tricycles and scooters, those generous cargo bikes and tandems.

The wheel. Turns, rolls, runs. With its moral values (the free wheel) and religious aspects (the sacred wheel), with its aesthetic and practical aspects (the spoke wheel, the radial wheel) but also melancholic (a flat tire) and dramatic (the wheel of the abandoned), with its altruism (the spare wheel). Over the centuries, the name of the inventor has been lost, not praised by everyone: "The one who invented the wheel was an idiot - ironically states the aphorist Sid Caesar -. It's the one who invented the other three that was a genius".

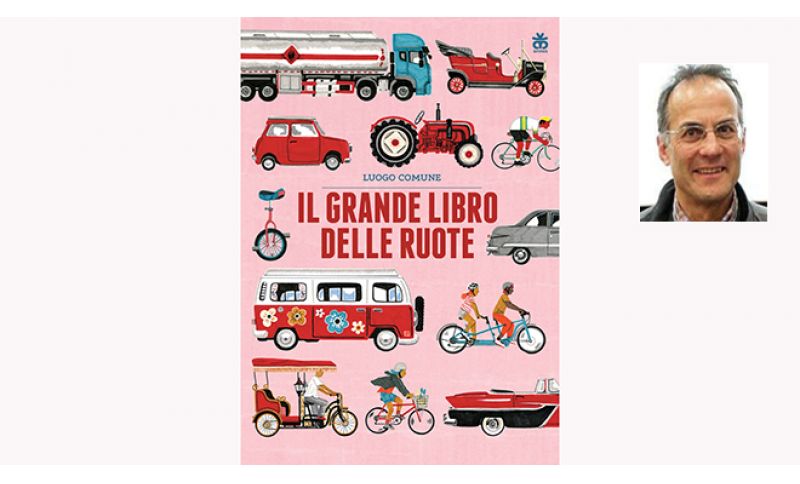

The publishing house Sinnos has dedicated to younger readers "The Great Book of Wheels", written and illustrated by Luogo Comune, the pseudonym of Jacopo Ghisoni, who loves to dismantle stereotypes and, indeed, common places through images on paper or even on walls. This time, in a large-format volume (32x24, hardcover, 48 pages, 137 vehicles and a total of 150 illustrations, 16 euros), Luogo Comune guides us through a traffic spanning nine thousand years, from Egyptian war chariots to a mother on her cargo bike carrying a daughter and a dog, followed by two other children on bikes. All smiling. Because unlike all other wheeled vehicles, the bicycle is the only one capable of giving happiness.

Se sei giá nostro utente esegui il login altrimenti registrati.